Medication-Food Interaction Checker

Ever taken a pill on an empty stomach and felt sick an hour later? You’re not alone. Many people don’t realize that what they eat - or don’t eat - when taking medicine can make a big difference in how their body handles it. Sometimes, food doesn’t just help the medicine work better. It can stop it from causing nausea, stomach pain, or worse. In fact, food-drug interactions are one of the most common, yet overlooked, reasons people end up in the hospital because of their medications.

Why Food Matters More Than You Think

Your stomach isn’t just a place where food breaks down. It’s a gatekeeper for your meds. When you swallow a pill, it needs to get absorbed into your bloodstream. That process depends on a lot of things: how full your stomach is, what’s in your food, how fast your gut moves, and even what enzymes are active in your intestines. Food slows down how quickly your stomach empties. Instead of rushing through in 15 minutes, it can take 2 to 4 hours. That extra time gives your body a better shot at absorbing the drug properly. For some medications, that means they work better. For others, it means they don’t wreck your stomach lining. Take ibuprofen, for example. It’s a common painkiller, but it’s also a known irritant. Studies show that 38% of people who take it on an empty stomach develop tiny tears in their stomach lining - invisible but real. When taken with food, that number drops to 12%. That’s more than a two-thirds reduction in damage. And it’s not just ibuprofen. Most NSAIDs - including naproxen and aspirin - follow the same pattern. Food acts like a buffer, protecting your stomach from harsh chemicals.When Food Makes Medicine Work Better

Not all drugs are meant to be taken on an empty stomach. Some actually need food to be absorbed at all. Griseofulvin, an antifungal used for stubborn nail or skin infections, is a classic case. If you take it without food, your body absorbs maybe 50% of the dose. Take it with a high-fat meal - think eggs, cheese, avocado - and absorption jumps to 80%. That’s not a small boost. It’s the difference between the drug working and you needing a second course of treatment. Same goes for some cholesterol-lowering statins. Simvastatin, for instance, becomes up to 15 times more potent when taken with a fatty meal. That sounds good - until you realize it can also mean more side effects like muscle pain or liver stress. That’s why your doctor might tell you to take it at night with dinner: you get the benefit without the risk of overdose. Even some mental health meds rely on food. Clozapine, used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, can cause extreme drowsiness. When taken with a high-fat meal, blood levels spike by 40-60%. That might help with symptom control - but it also means you could fall asleep behind the wheel. Timing matters.When Food Blocks Medicine - And Why It’s Dangerous

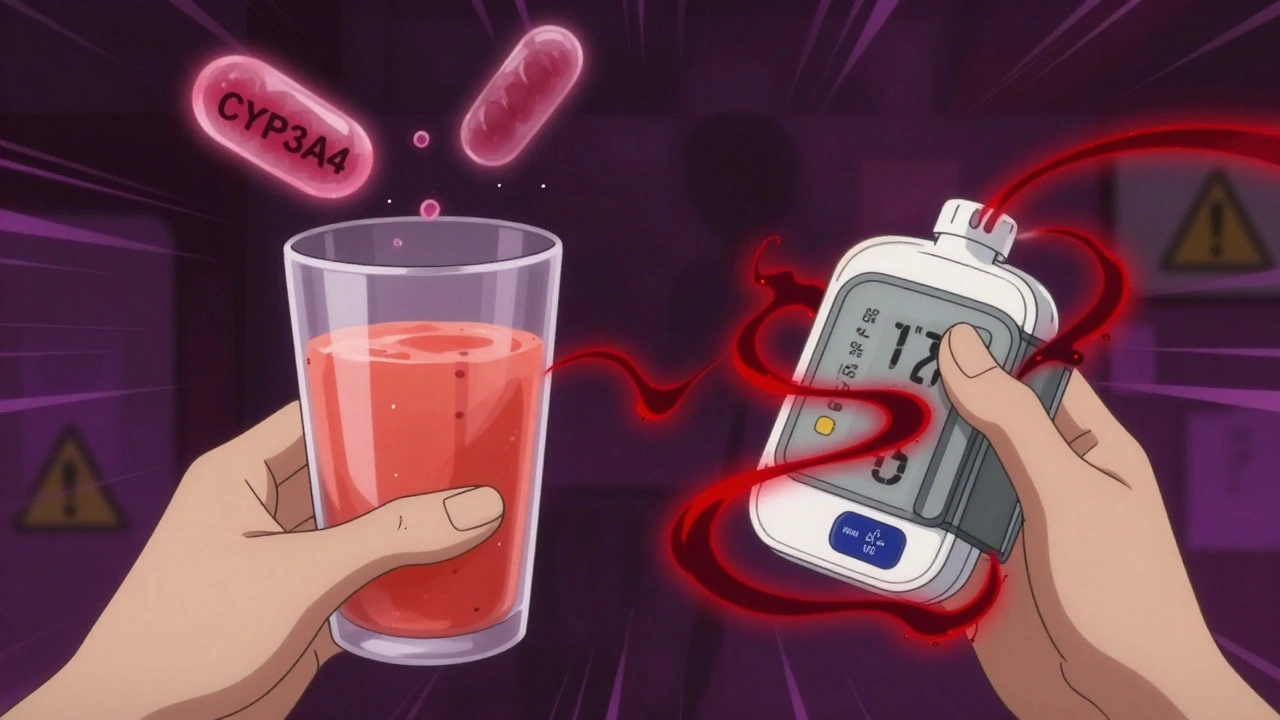

Food isn’t always a friend. Sometimes, it’s a blocker. Calcium is one of the biggest culprits. Found in milk, yogurt, cheese, and even fortified orange juice, calcium binds to certain antibiotics like tetracycline and ciprofloxacin. That binding stops your body from absorbing them. Studies show absorption can drop by up to 50%. That means the infection doesn’t get treated - and you risk developing drug-resistant bacteria. Then there’s grapefruit juice. It’s not just a health trend. It’s a pharmacological wildcard. Grapefruit contains compounds that shut down an enzyme called CYP3A4 - the same enzyme that breaks down about half of all prescription drugs. When that enzyme is blocked, drugs like cyclosporine (used after organ transplants) or certain blood pressure meds can build up to dangerous levels. One glass of grapefruit juice can do this for 24 to 72 hours. Even if you take your pill hours after the juice, the effect lingers. Levothyroxine, the go-to treatment for underactive thyroid, is another example. It needs to be taken on an empty stomach, at least an hour before breakfast. Why? Because calcium, iron, soy, and even coffee can cut its absorption by 30-55%. Patients who take it with their morning oatmeal or smoothie often end up with fatigue, weight gain, or depression - not because their thyroid is worse, but because the medicine isn’t getting in.

What About Diabetes and Warfarin?

Some medications don’t just interact with food - they interact with your whole diet. Metformin, the most common drug for type 2 diabetes, causes nausea, diarrhea, and stomach cramps in about 63% of people who take it without food. Take it with a meal, and those side effects drop to 18%. That’s why doctors always say: “Take with your largest meal.” It’s not just about comfort - it’s about sticking with the treatment. Warfarin, a blood thinner, is trickier. It doesn’t interact with food the way antibiotics do. Instead, it reacts to vitamin K - found in spinach, kale, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts. Vitamin K helps your blood clot. Warfarin fights that. If you eat a salad every day, your INR (a blood test that measures clotting time) stays steady. But if you skip greens for a week, your blood gets thinner - and you risk bleeding. Eat too many greens one day? Your blood thickens - and you risk a clot. Consistency is everything. You don’t have to avoid leafy greens. You just have to eat about the same amount every day.What Does ‘With Food’ Really Mean?

If your prescription says “take with food,” it doesn’t mean a cracker. It means at least 250-500 calories. That’s a sandwich, a bowl of oatmeal with nuts and fruit, or a small plate of eggs and toast. “Take on an empty stomach” means 1 hour before or 2 hours after eating. That’s not just “don’t eat right before.” It means no snacks, no coffee with cream, no gum. Even small amounts of food can interfere. And here’s the kicker: many people don’t know this. A Mayo Clinic study found that 68% of patients over 65 had no idea their meds needed specific food timing. Only 22% got clear instructions from their doctor. That’s a huge gap.

How to Get It Right

Managing multiple meds with different food rules is hard. But it’s doable. Start with your pharmacist. They’re trained to spot food-drug conflicts. Ask: “Should I take this with food? What kind? What should I avoid?” Don’t assume your doctor told you everything. Most visits are 10 minutes long. Pharmacists have more time. Use a simple tracker. Write down each med, whether it needs food or not, and what time you take it. Apps like Medisafe send reminders and flag potential conflicts. In clinical trials, they’ve cut food-drug errors by 37%. Create a color-coded system. Green = take with food. Red = take on empty stomach. Yellow = flexible. Tape it to your fridge. Or set a note on your phone. If you’re on five or more meds - common for people with arthritis, heart disease, or diabetes - ask for a medication review. Many hospitals now offer free sessions with clinical pharmacists. They’ll map out your whole regimen and tell you exactly when to eat and when to wait.The Bigger Picture

Food-drug interactions aren’t just about discomfort. They cost the U.S. healthcare system $177 billion a year in hospital visits, extra tests, and failed treatments. The FDA now requires food-effect studies for nearly 80% of new drugs. Labels are clearer. Pharmacies are adding warning stickers. CVS and Walgreens now use AI to flag risks right on your prescription bag. But technology won’t fix everything. You still have to pay attention. The most powerful tool you have is knowledge. Knowing that grapefruit juice can make your blood pressure med too strong. Knowing that calcium pills can cancel out your antibiotic. Knowing that skipping breakfast might make your thyroid med useless. It’s not complicated. It’s just specific. And it’s worth getting right.Can I take my pill with just a sip of milk?

No. A sip of milk isn’t enough. If your medicine needs food, aim for at least 250-500 calories - like a slice of toast with peanut butter, a small yogurt with fruit, or a handful of nuts and an apple. A small amount of milk or juice won’t trigger the right stomach response and may still interfere with absorption, especially for antibiotics or thyroid meds.

Is it okay to take medicine with coffee?

It depends. Coffee can reduce absorption of some drugs like levothyroxine, iron supplements, and certain antibiotics. Even black coffee can interfere. If your med needs an empty stomach, wait at least an hour after coffee. If you take it with food, avoid coffee for at least 30 minutes after. For most meds, water is the safest choice.

Why does grapefruit juice affect some drugs but not others?

Grapefruit blocks an enzyme called CYP3A4, which breaks down certain drugs in the gut. Drugs like simvastatin, cyclosporine, and some blood pressure meds rely on this enzyme. Others, like pravastatin or lisinopril, don’t. That’s why you can drink grapefruit juice with some meds and not others. Always check your label or ask your pharmacist - don’t guess.

What if I forget to take my medicine with food?

If you usually take it with food and forgot, don’t panic. If it’s been less than an hour, eat something and take it now. If it’s been longer, skip the dose and wait until your next scheduled time - unless your doctor says otherwise. Never double up. Missing one dose is less risky than overdosing because you took it with food later.

Do over-the-counter meds have food interactions too?

Yes. Even common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, aspirin, and antacids can cause stomach upset if taken empty. Some antacids with calcium or magnesium can block antibiotics like tetracycline. Always read the label. If it says “take with food” or “may cause stomach upset,” treat it like a prescription.

Anna Roh

December 7, 2025 AT 16:57So basically if I take my ibuprofen with a single chip, I’m basically doing yoga for my stomach? Cool.

Simran Chettiar

December 7, 2025 AT 17:28It is fascinating how the body operates as a complex ecosystem where even the smallest dietary choice can alter the pharmacokinetics of a compound ingested. The stomach is not merely a vessel for digestion but a dynamic regulatory organ that modulates drug absorption through gastric emptying rates, pH fluctuations, and enzymatic activity. Food, particularly fats, can enhance bioavailability by stimulating bile secretion and lymphatic transport, while calcium and polyphenols may chelate or inhibit transporters. This is not mere folklore-it is pharmacology in action, and yet most patients are left to guess. We must institutionalize education on this, not just as an afterthought but as core clinical literacy.

Richard Eite

December 9, 2025 AT 08:04Americans are too lazy to read labels. I take my meds with water and a fistful of beef jerky. If it makes me sick I just take more. Problem solved.

Katherine Chan

December 9, 2025 AT 22:06This is so helpful I wish I’d known this years ago. I used to take my thyroid med with coffee and wonder why I was always exhausted. Now I drink my coffee after breakfast and feel like a new person. Small changes really do matter 💪

Philippa Barraclough

December 11, 2025 AT 03:57The distinction between food that enhances absorption and food that inhibits it is clinically significant yet routinely undercommunicated. The pharmacokinetic variability induced by dietary components-particularly in drugs with narrow therapeutic indices such as warfarin or levothyroxine-demands structured patient education. The fact that 68% of elderly patients are unaware of these interactions suggests systemic failure in medication counseling. While AI-driven pharmacy alerts are a step forward, they cannot replace human dialogue. A pharmacist’s brief explanation during pickup may be the only time a patient receives clear, individualized guidance. This is not a technical problem-it is a communication crisis.

Tim Tinh

December 11, 2025 AT 11:14Man I used to take my simvastatin with a bagel and orange juice and wonder why I felt like a zombie. Then my pharmacist told me to take it with avocado toast instead. Game changer. Also grapefruit juice is evil. Don’t do it. I learned the hard way.

Olivia Portier

December 12, 2025 AT 07:38My mom took her antibiotics with yogurt every day and kept getting sick. Turns out the calcium was blocking it. She thought yogurt was ‘healthy’ so it must be fine. Turns out health food can be a drug villain. Now she takes her meds with plain water and eats yogurt 3 hours later. We all need a little pharmacist love in our lives.

Rich Paul

December 13, 2025 AT 01:11Let me break this down for the laypeople: CYP3A4 inhibition by furanocoumarins in grapefruit alters first-pass metabolism, leading to supratherapeutic plasma concentrations of substrates like cyclosporine and statins. The AUC increases up to 500% in some cases. This isn’t anecdotal-it’s in the FDA’s black box warning database. If you’re on anything with a half-life under 8 hours and you’re drinking grapefruit juice, you’re playing Russian roulette with your liver.

Lauren Dare

December 14, 2025 AT 21:38Wow. So the reason my doctor keeps changing my warfarin dose is because I eat kale? Not because I’m a bad patient? Just because I didn’t know spinach and broccoli are basically vitamin K landmines? Thanks for the passive-aggressive education, post.

Gilbert Lacasandile

December 16, 2025 AT 21:09I appreciate this. I’ve been taking my metformin on an empty stomach because I thought that’s what ‘fasting’ meant. Now I know why I was always nauseous. I’ll start taking it with dinner. Thanks for the clarity.

William Umstattd

December 17, 2025 AT 18:53If you’re not taking your meds exactly as prescribed, you’re not just risking your health-you’re disrespecting science, your doctor, and the billions spent on clinical trials. This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a medical imperative. Stop treating your body like a lab experiment you haven’t read the protocol for.

Andrea Beilstein

December 19, 2025 AT 04:07It’s funny how we trust our phones to tell us when to eat and when to sleep but we don’t trust the label on our own medicine. Maybe we’ve forgotten that the body isn’t a machine you can hack with willpower. It’s a living system that responds to rhythm, timing, and context. Food isn’t just fuel-it’s language. And when you speak the wrong dialect to your meds, they don’t understand you.

om guru

December 21, 2025 AT 01:43Take medication as directed. Consult pharmacist. Do not assume. Knowledge prevents hospitalization. Discipline saves lives. Simple. Direct. Effective.