When a medication changes the way your heart beats, it’s not always obvious. You might feel fine, but inside, your heart’s electrical system could be on shaky ground. That’s where QT prolongation comes in - a hidden danger in some of the most commonly prescribed drugs. It doesn’t cause symptoms on its own, but it can trigger a deadly rhythm called torsades de pointes, which can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. The good news? You don’t need to panic. You just need to know which drugs to watch for - and when to ask your doctor for an ECG.

What Exactly Is QT Prolongation?

The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) to recharge between beats. When that interval gets too long - usually defined as a corrected QT (QTc) over 500 milliseconds - your heart becomes electrically unstable. This doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly collapse. But it does mean your heart is more likely to slip into a dangerous, chaotic rhythm called torsades de pointes. Once that starts, it can turn into ventricular fibrillation - and that’s when the heart stops pumping blood. This isn’t rare. In 2013, the FDA found that 22% of the 205 drugs they reviewed caused measurable QT prolongation. By 2018, crediblemeds.org listed 223 drugs with known, possible, or conditional risk of triggering this problem. Most of these drugs block a specific potassium channel in the heart called hERG. That’s the same channel that keeps the heart’s electrical signal moving smoothly. Block it, and the signal drags - leading to a longer QT interval.Which Medications Are the Biggest Culprits?

Not all QT-prolonging drugs are created equal. Some are high-risk, some are low-risk, and some only become dangerous when mixed with other drugs or in certain patients. High-risk drugs include:- Class Ia antiarrhythmics - quinidine and procainamide. These were among the first drugs linked to QT prolongation. Quinidine causes torsades in about 6% of users.

- Class III antiarrhythmics - sotalol, dofetilide, ibutilide. These are designed to slow the heart’s rhythm, but they carry a 2-5% risk of torsades. Sotalol is especially risky at higher doses.

- Methadone - used for pain and opioid addiction. Risk spikes above 100 mg daily. Even at lower doses, it’s dangerous if combined with other QT-prolonging drugs.

- Amiodarone - while it prolongs QT significantly, its actual torsades risk is low (under 1%) because it blocks multiple channels, not just hERG.

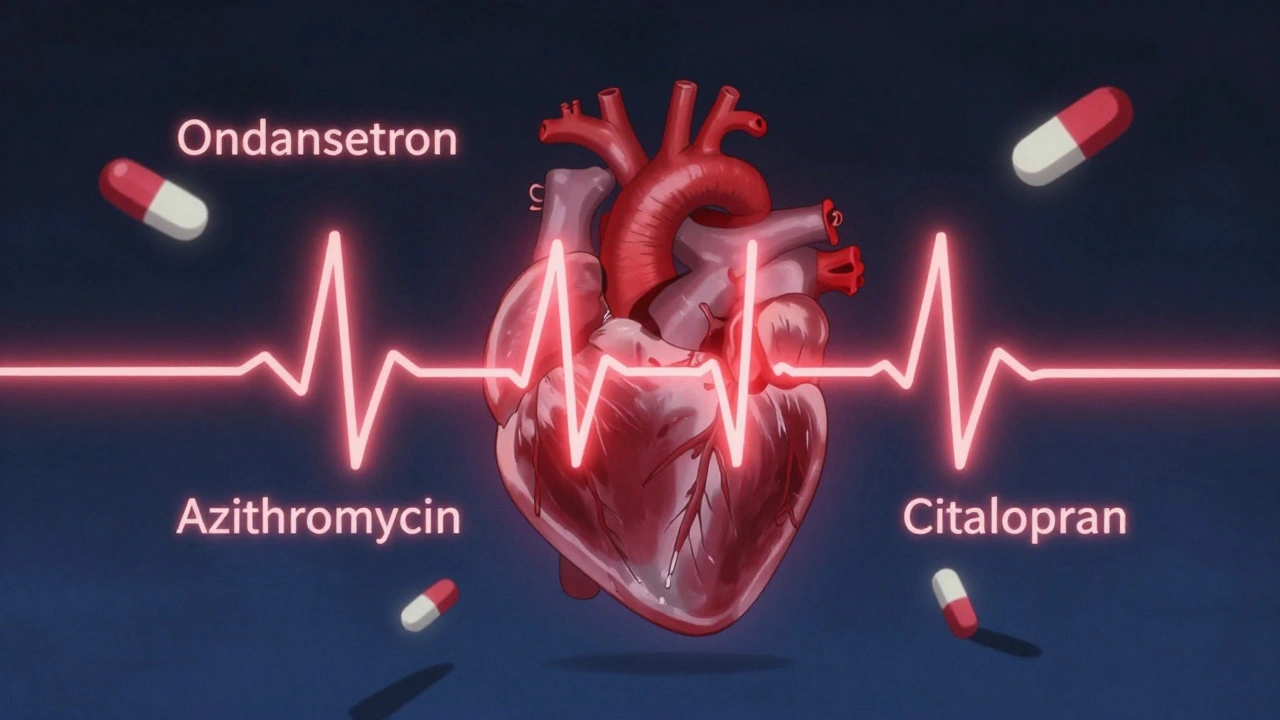

- Antibiotics - erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin. Erythromycin can lengthen QT by 15-25 ms, especially if taken with drugs that slow its breakdown (like grapefruit juice or certain antifungals).

- Antifungals - fluconazole. Risk increases with doses over 400 mg daily.

- Antipsychotics - haloperidol, ziprasidone. Ziprasidone has a black box warning for ventricular arrhythmias. Haloperidol is often used in emergency rooms for agitation - but if given with ondansetron, the risk multiplies.

- Antiemetics - ondansetron (Zofran). Used for nausea, especially after chemo or surgery. It’s one of the top drugs involved in documented torsades cases.

- Antidepressants - citalopram and escitalopram. The FDA capped citalopram at 40 mg daily (20 mg if over 60) because of dose-dependent QT prolongation.

Why Are Some People at Higher Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. The biggest risk factors include:- Female sex - women make up about 70% of documented torsades cases. Hormonal differences make their hearts more sensitive to hERG blockade.

- Age over 65 - kidneys and liver slow down, so drugs build up in the body longer.

- Low potassium or magnesium - electrolyte imbalances make the heart more excitable. This is common in people on diuretics, with eating disorders, or after vomiting/diarrhea.

- Heart disease - especially heart failure or prior heart attack. Scarred tissue creates electrical shortcuts that can trigger arrhythmias.

- Genetic factors - about 30% of drug-induced torsades cases involve hidden mutations in the hERG gene. You might not know you have it until a drug triggers a crisis.

- Multiple QT-prolonging drugs - taking two or more drugs that prolong QT is the most common scenario in documented cases. One study found 68% of torsades cases involved two or more such drugs.

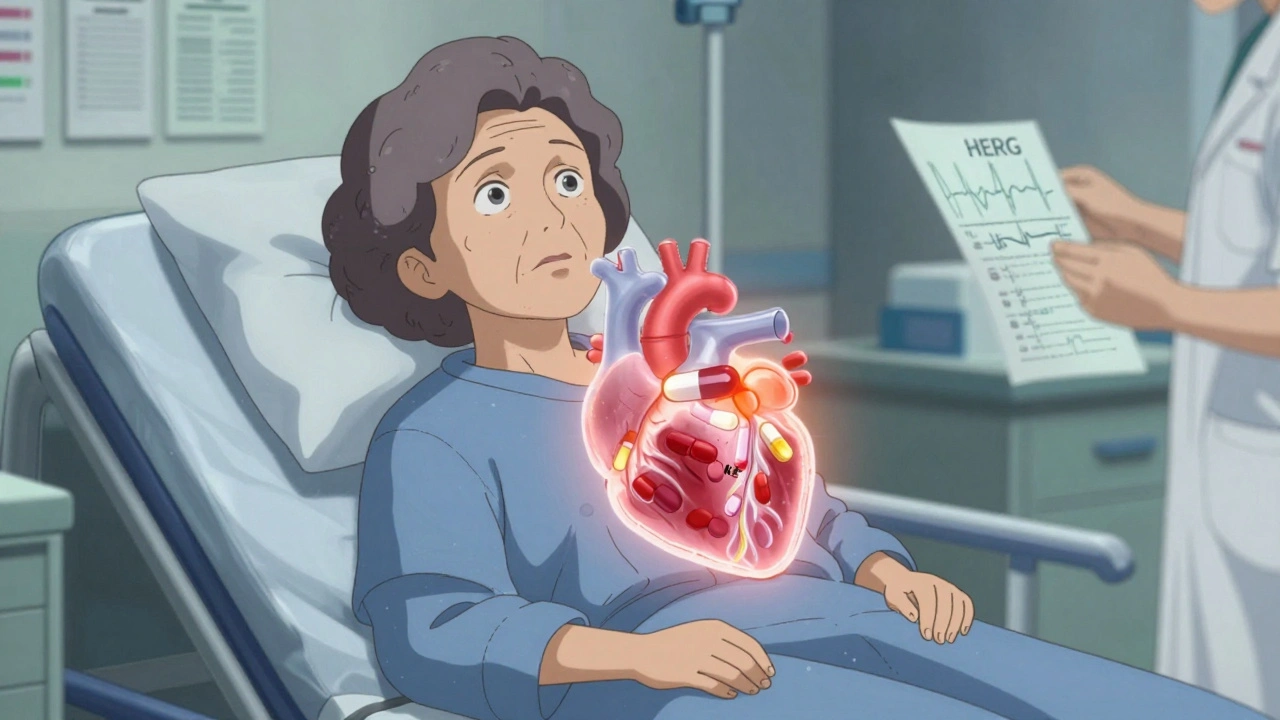

A real-world example: a 65-year-old woman with gastroenteritis gets azithromycin and ondansetron. Her baseline QTc was 440 ms. Within 24 hours, it jumps to 530 ms. She collapses. That’s not a fluke - it’s a predictable cascade.

When Should You Get an ECG?

You don’t need an ECG for every new prescription. But you should ask for one if:- You’re starting a high-risk drug like sotalol, methadone, or dofetilide.

- You’re over 65 and starting any new medication with QT risk.

- You’re taking more than one drug that prolongs QT - even if each is low risk on its own.

- You have a history of heart problems, low electrolytes, or unexplained fainting.

- You’re on a high dose of citalopram, fluconazole, or ondansetron.

Guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and Medsafe (New Zealand) recommend checking QTc within 3-7 days after starting a high-risk drug or increasing the dose. If the QTc goes over 500 ms, or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline, the drug should be stopped - unless there’s no alternative and the benefit outweighs the risk.

What About Newer Drugs?

The drug development world is changing. In 2013, the FDA launched CiPA - a new testing system that doesn’t just measure QT prolongation. It looks at how drugs affect multiple heart ion channels and uses computer models to predict real-world risk. This has already led to 22 drug failures since 2016, costing billions - but it’s saving lives. New drugs like retatrutide (an obesity treatment approved in late 2023) now come with QT prolongation warnings. Of the 27 tyrosine kinase inhibitors used in cancer treatment, 12 carry QT risk warnings. These aren’t old drugs - they’re cutting-edge therapies with hidden dangers.How to Stay Safe

Here’s what you can do:- Know your meds - Check crediblemeds.org. It’s free, updated quarterly, and ranks drugs by risk level: Known Risk, Possible Risk, Conditional Risk.

- Ask your pharmacist - When you get a new prescription, ask: “Does this affect my heart rhythm?” Most pharmacists can access drug interaction databases that flag QT risks.

- Don’t mix drugs - Avoid combining antibiotics like azithromycin with ondansetron or antipsychotics. Even if your doctor didn’t warn you, it’s a known dangerous combo.

- Get electrolytes checked - If you’re on diuretics or have had vomiting/diarrhea, ask for a blood test for potassium and magnesium.

- Monitor your symptoms - Dizziness, fainting, palpitations, or sudden fatigue after starting a new drug? Don’t wait. Get an ECG.

Some doctors argue that routine ECGs for low-risk drugs are overkill. After all, the chance of torsades from a single low-risk drug is less than 1 in 10,000 per year. But when you combine risk factors - a woman over 65 on citalopram and azithromycin with low potassium - the risk isn’t theoretical anymore. It’s real.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. In 2023, scientists identified 23 genetic variants that explain 18% of why some people are more sensitive to QT prolongation. AI tools are being trained to spot subtle ECG patterns that predict torsades before the QT interval even looks abnormal. One 2024 study showed an AI algorithm predicting risk with 89% accuracy. Meanwhile, hospitals using electronic health record systems with built-in QT risk alerts have cut dangerous drug combinations by 58%. That’s not magic - it’s smart technology catching what humans miss.Final Thought

QT prolongation isn’t something you can feel. But it’s something you can prevent. Most cases happen because of simple, avoidable mistakes: combining two safe drugs, ignoring electrolytes, or not checking ECGs in high-risk patients. You don’t need to avoid all medications. You just need to be informed. Ask questions. Get tested when needed. And never assume a drug is safe just because it’s commonly prescribed.Can a single drug cause torsades de pointes?

Yes, but it’s rare with low-risk drugs. Most cases happen when multiple risk factors combine - like taking a QT-prolonging drug while having low potassium, being female, over 65, or on another interacting medication. High-risk drugs like sotalol or quinidine can trigger torsades even alone, especially at high doses.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

No. Mild prolongation (QTc 450-499 ms) is common and often harmless, especially in athletes or people with slow heart rates. Danger starts when QTc exceeds 500 ms or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline. That’s when the risk of torsades rises sharply.

Can I take ondansetron if I’m on citalopram?

It’s risky. Both drugs prolong the QT interval. Together, they can push QTc over 500 ms, especially in older adults or those with low electrolytes. If you need nausea relief while on citalopram, ask your doctor about alternatives like metoclopramide or non-drug options. Avoid combining these unless absolutely necessary and only with ECG monitoring.

Do I need to get an ECG before taking antibiotics?

Not routinely. But if you’re over 65, have heart disease, take other QT-prolonging drugs, or have low potassium/magnesium, yes. Erythromycin and clarithromycin are higher risk than azithromycin. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor or pharmacist to check your drug list against crediblemeds.org.

What should I do if I feel dizzy after starting a new medication?

Don’t ignore it. Dizziness, fainting, or a racing heartbeat can be early signs of a dangerous heart rhythm. Stop the medication and get an ECG immediately. Bring your full medication list - including supplements and over-the-counter drugs - to your appointment. Many QT-prolonging drugs are found in cough syrups, antihistamines, or herbal products.

Are there any safe alternatives to QT-prolonging drugs?

Often, yes. For nausea: metoclopramide or promethazine may be safer than ondansetron. For depression: sertraline or bupropion have lower QT risk than citalopram. For infection: amoxicillin is safer than azithromycin if appropriate. Always ask your doctor: "Is there a lower-risk option?" Don’t assume the first prescribed drug is the only choice.

James Kerr

December 2, 2025 AT 02:08Wow, this is seriously eye-opening. I had no idea Zofran could mess with my heart like that. I’ve taken it after surgery and didn’t think twice. Gonna check my meds list now. Thanks for breaking it down so clearly 😊

shalini vaishnav

December 2, 2025 AT 04:20How can you trust Western medicine when they approve drugs with such blatant risks? In India, we’ve known for decades that antibiotics and antiemetics shouldn’t be mixed. This is just corporate greed masked as science. No ECG? No thanks. We don’t need your flawed guidelines.

vinoth kumar

December 2, 2025 AT 20:22Really appreciate this breakdown! I’m a pharmacist in Bangalore and we see this all the time - patients on citalopram getting azithromycin for a cold. We flag it, but so many don’t listen. I always tell them: ‘Your heart doesn’t care if the drug is ‘common’ - it just reacts.’ If you’re on two QT drugs, get a basic ECG. It takes 5 minutes. Could save your life.

bobby chandra

December 2, 2025 AT 20:31This isn’t just medical info - it’s a wake-up call wrapped in a clinical report. We’ve normalized ‘safe’ meds like Zofran and azithromycin like they’re candy. But your heart? It’s not a vending machine. It’s a high-voltage orchestra. One wrong note - a potassium dip, a combo pill, a silent gene - and the whole symphony goes silent. Don’t wait for the crash. Check your QT. Know your meds. Your life isn’t a gamble.

Archie singh

December 3, 2025 AT 02:31Everyone’s panicking over QT prolongation like it’s a new plague. Newsflash: the FDA is a broken institution. They approved methadone for pain AND addiction while knowing the risk. And now they want you to get an ECG for every antibiotic? That’s bureaucratic overreach disguised as safety. You’re being manipulated into medical theater. Stop trusting the system. Trust your body.

Gene Linetsky

December 4, 2025 AT 16:29They don’t want you to know this but every single QT-prolonging drug on the list is tied to Big Pharma’s profit model. The hERG channel? They knew about it since the 90s. They buried the data. The FDA’s CiPA program? A PR stunt. They’re still approving drugs with QT risk because they’re profitable. And now they’re pushing ECGs so they can bill you extra. This isn’t medicine - it’s a money machine. Google ‘hERG suppression patent filings’ and tell me I’m wrong.

Kidar Saleh

December 6, 2025 AT 04:06As someone who’s worked in UK emergency medicine for 20 years, I’ve seen this play out too many times. A woman in her 70s, on citalopram, gets a course of clarithromycin for a chest infection. No electrolytes checked. No ECG. She collapses in the waiting room. We resuscitated her - but her heart was never the same. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening in NHS hospitals right now. Please, if you’re over 65, take this seriously. Your GP might not know - but you can.

Chloe Madison

December 6, 2025 AT 10:44Thank you for writing this with such precision and care. As a cardiology nurse, I’ve seen the quiet, devastating aftermath of torsades - families who thought ‘it was just a bad reaction’ when it was actually preventable. Please don’t underestimate the power of a simple blood test for potassium and magnesium. Or asking your pharmacist, ‘Is this safe with my other meds?’ Knowledge is your best defense. You are not being paranoid - you’re being proactive. And that’s not just smart - it’s heroic.