When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just have a patent. It has patent exclusivity and market exclusivity-two different shields that keep generics away. People often mix them up, but they’re not the same. One comes from the patent office. The other comes from the FDA. And the difference can mean years of extra monopoly pricing for drug companies-and delayed access for patients.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Right to Block Copycats

A patent is a legal tool granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It gives the inventor the right to stop anyone else from making, selling, or using their invention. For drugs, that usually means the exact chemical formula-the active ingredient. This is called a composition of matter patent, and it’s the strongest kind.

Patents last 20 years from the day they’re filed. But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years just to get approved by the FDA. That means by the time a drug actually hits shelves, it might only have 5 to 8 years of real market protection left. That’s not enough to recoup the $2.3 billion it typically costs to develop a new drug.

That’s why patent extensions exist. The law lets drugmakers apply for Patent Term Extension (PTE) to make up for time lost during FDA review. But there’s a cap: you can’t extend the patent past 14 years after the drug is approved. And even then, you need to prove the delay was due to regulatory review-not your own mistakes.

Patents can also cover how the drug is made, how it’s taken, or what condition it treats. These are called secondary patents. They’re weaker than composition patents, but companies pile them on. One drug might have 10, 20, even 50 patents covering every tiny detail. This tactic, called evergreening, keeps generics off the market long after the core patent expires.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Secret Weapon

Market exclusivity is not a patent. It’s a regulatory gift from the FDA. It doesn’t care if the drug is new or old. It cares if the company submitted new clinical data to get approval. And if they did, the FDA won’t let anyone else copy it for a set time-no matter what patents say.

The most common type is New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity. If a drug has never been approved before, the FDA gives it 5 years of protection. During that time, no generic can even file an application. After 5 years, generics can apply-but they still can’t use the original company’s clinical data to prove safety. They have to run their own trials, which is expensive and slow.

Then there’s orphan drug exclusivity. If a drug treats a rare disease (fewer than 200,000 patients in the U.S.), the FDA grants 7 years of exclusivity-even if there’s no patent. This was meant to help small companies develop drugs for neglected conditions. But some companies have used it to lock in pricing on old drugs repurposed for rare diseases. The classic example is colchicine, a 3,000-year-old remedy for gout. In 2010, a company got 10 years of exclusivity for a reformulated version. The price jumped from 10 cents to $5 per pill.

Biologics-complex drugs made from living cells-get 12 years of exclusivity under the BPCIA law of 2009. That’s longer than most patents. And if a company does extra pediatric testing, they get a 6-month bonus on top of any existing exclusivity. That 6-month bump has earned drugmakers over $15 billion since 1997.

And here’s the kicker: the first generic company to challenge a patent and win gets 180 days of exclusivity. That’s a gold mine. One company can corner the entire generic market for half a year. That period is worth up to $500 million in extra revenue.

How They Work Together (and When They Don’t)

Patents and market exclusivity can run at the same time. Or one can end while the other keeps going. That’s why you’ll see some drugs with no patents left but still no generics on the shelf. The FDA’s exclusivity is still active.

According to FDA data from 2021:

- 38.4% of branded drugs had only patents-no exclusivity

- 5.2% had only exclusivity-no patents

- 27.8% had both

- 28.6% had neither

That 5.2% is critical. It means some drugs are protected purely by regulatory rules. No patent? No problem. The FDA still blocks competitors. That’s why companies now focus more on exclusivity than patents. For small biotech firms, 73% rely on exclusivity as their main protection, especially for reformulated drugs or biologics that can’t be patented easily.

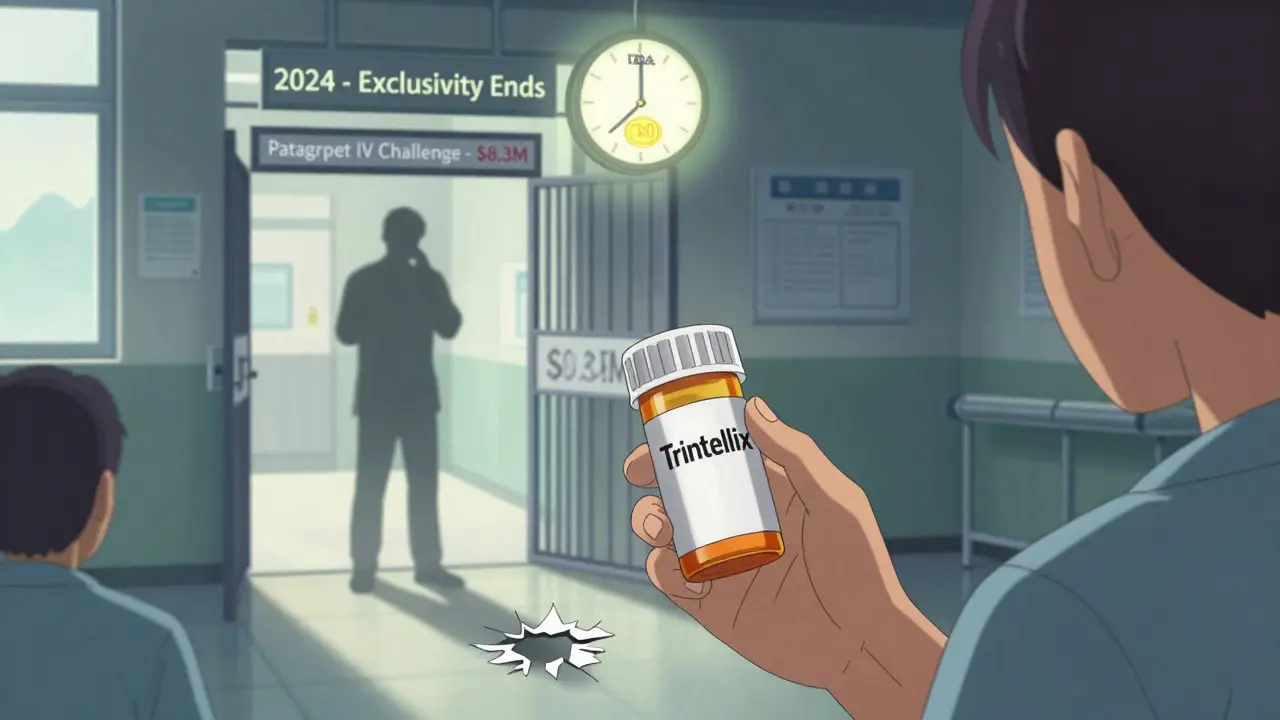

Take Trintellix, an antidepressant. Its main patent expired in 2021. But because it had 3 years of exclusivity, generics couldn’t enter until 2024. Teva Pharmaceuticals lost an estimated $320 million in potential sales during that gap.

Why the Confusion? Real-World Mistakes

Many companies-especially small ones-think a patent = market control. They’re wrong. A patent doesn’t stop the FDA from approving a generic. Only exclusivity does.

A 2022 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 43% of small biotech firms made at least one mistake because they confused the two. One company spent $1.7 million extra developing a drug, thinking its patent would block competition. It didn’t. The FDA approved a generic months later because there was no exclusivity.

Even big companies mess up. Between 2018 and 2022, 22% of innovator companies failed to claim all the exclusivity they were legally entitled to. On average, they left 1.3 years of protection on the table. That’s free money they didn’t get.

And for generics? The process is a minefield. To challenge a patent, a generic company must file a Paragraph IV certification. That’s a legal bomb. It triggers lawsuits. The average cost per challenge? $8.3 million. And if they lose, they get nothing. That’s why only a handful of companies have the resources to play this game.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The rules are shifting. In 2023, the FDA launched a new public dashboard that shows every drug’s exclusivity status in real time. That’s a game-changer. Generic companies can now see exactly when a drug will open up-no more guessing.

The PREVAIL Act, introduced in 2023, proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. If it passes, it could open the door for more competition in the cancer and autoimmune drug markets.

And the FDA is now requiring more detailed justifications for exclusivity claims. Starting January 1, 2024, companies must prove their clinical data was truly new-not just a tweak of old studies. That could shut down some of the shady exclusivity grabs.

McKinsey predicts that by 2027, regulatory exclusivity will account for over half of all drug protection time. Patents are becoming harder to enforce. Courts are striking down secondary patents. Exclusivity is the new battleground.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient: don’t assume a drug will go generic when its patent expires. Check if it has exclusivity. That 6-month pediatric extension? That could delay your cheaper option for another half-year.

If you’re a pharmacist or provider: know the difference. When a patient asks why their brand-name drug still costs $300 when the patent’s expired, you can explain: it’s not about the patent. It’s about the FDA’s clock.

If you’re in the industry: don’t rely on patents alone. Build your strategy around exclusivity. File for orphan status. Do the pediatric studies. Claim every day you’re owed. The money is in the regulatory details, not the legal filings.

Patents are about invention. Market exclusivity is about data. One protects the idea. The other protects the proof. And in today’s drug market, the proof matters more than the idea.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. The FDA can grant market exclusivity even if a drug has no patent protection. For example, orphan drugs get 7 years of exclusivity regardless of patent status. In 2021, 5.2% of branded drugs had exclusivity but no patents. Colchicine is a well-known case-its original patent expired decades ago, but regulatory exclusivity kept generics off the market for 10 years.

How long does FDA market exclusivity last?

It varies by drug type. New Chemical Entities (NCEs) get 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7 years. Biologics get 12 years. Pediatric exclusivity adds 6 months to any existing protection. First generic applicants who successfully challenge a patent get 180 days. These periods start when the drug is approved by the FDA, not when the patent was filed.

Does patent extension count as market exclusivity?

No. Patent extension (PTE) extends the legal patent term, but it’s still a patent. Market exclusivity is a separate FDA rule. A drug can have both: a 20-year patent extended by 3 years, plus 5 years of NCE exclusivity. The FDA doesn’t care about patent extensions-it only enforces its own exclusivity rules.

Why do generics still cost so much even after exclusivity ends?

After exclusivity ends, generics can enter-but they don’t always. Sometimes only one or two companies make the drug, so competition stays low. Other times, the manufacturing is complex, or the profit margin is thin. In some cases, the brand-name company still controls distribution or uses tactics like “authorized generics” to keep prices high. Exclusivity ends, but market power doesn’t always disappear.

How can I check if a drug still has exclusivity?

The FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard, launched in September 2023, is the best public tool. It shows all active exclusivity periods for approved drugs. You can search by brand name or active ingredient. The Orange Book lists patents, but only the Exclusivity Dashboard shows FDA-specific protections. It’s free, updated daily, and designed for patients, pharmacists, and generic manufacturers.

Haley Parizo

January 3, 2026 AT 01:25Patents are for inventors. Exclusivity is for lobbyists. The FDA isn't protecting patients-it's protecting profit margins disguised as public health. We call this innovation. It's just corporate feudalism with a white coat.

And don't get me started on orphan drug abuse. Colchicine for $5 a pill? That’s not medicine. That’s extortion wrapped in a clinical trial.

They’re not selling drugs. They’re selling time. And we’re paying for it in suffering.

12 years for biologics? Try 12 years of people dying while shareholders cash in.

It’s not capitalism. It’s legalized theft with a FDA stamp.

Ian Detrick

January 4, 2026 AT 01:13This is one of the clearest breakdowns I’ve seen on how the system actually works. Most people think patents = monopoly, but the real power move is exclusivity. The FDA’s rules are the hidden levers.

That 5.2% of drugs with exclusivity but no patents? That’s the future. Companies are shifting from IP law to regulatory strategy. Smart move. Courts are killing secondary patents left and right.

And the 180-day generic window? That’s the wild west. One company gets rich, everyone else waits. It’s not competition-it’s a lottery rigged by paperwork.

Angela Fisher

January 4, 2026 AT 07:18THEY KNOW. THEY KNOW WHAT THEY’RE DOING. 🤫

Do you think the FDA really cares about patients? NO. They’re in bed with Big Pharma. The dashboard? A distraction. A magic show to make you think transparency exists.

Remember when they approved that ‘new’ version of aspirin with a fancy coating? 7-year exclusivity. SEVEN YEARS. For ASPIRIN.

They’re not protecting innovation-they’re protecting the illusion of innovation.

And the pediatric extension? That’s not for kids. That’s for CEOs on their third yacht.

EVERYTHING IS A SCAM. EVERY. SINGLE. DAY.

They’re lying to you. And they’re lying to me. And we’re all paying for it. 💔

Shruti Badhwar

January 5, 2026 AT 13:15While the U.S. system is deeply flawed, I find it interesting how India’s generic manufacturing sector has become a global lifeline precisely because of these loopholes.

Many drugs that remain monopolized in America due to exclusivity are available as affordable generics in India within months of patent expiry-even if U.S. exclusivity is still active.

It’s not just a legal difference-it’s a moral one. The U.S. prioritizes corporate ROI over human access. India prioritizes survival over shareholder dividends.

Perhaps the real question isn’t how exclusivity works-but why we accept it as normal.

Brittany Wallace

January 6, 2026 AT 16:44I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been trying to explain this to my mom for years-why her antidepressant still costs $300 even though the patent expired.

She thought it was a glitch. I thought I was crazy.

Now I can send her this and say: ‘This is why.’

It’s not about being anti-pharma. It’s about being pro-human.

And honestly? I’m tired of being told to be grateful for ‘medical progress’ when progress means my neighbor can’t afford insulin.

Thank you for making the invisible visible. 🙏

Liam Tanner

January 7, 2026 AT 09:17For anyone new to this: think of patents as the lock on the door. Exclusivity is the guard standing in front of the door saying, ‘No one’s coming in-even if they have the key.’

And the guard answers to the FDA, not the patent office.

That’s why you can have a drug with zero patents left and still no generics. The guard is still there.

Big Pharma doesn’t need to win in court anymore. They just need to file the right paperwork.

It’s not innovation. It’s bureaucracy as a weapon.

Palesa Makuru

January 8, 2026 AT 02:30Oh sweetie, you’re so cute thinking this is about science. It’s not. It’s about who owns the paperwork.

I worked at a pharma firm in Cape Town. We’d buy expired drugs, repackage them with a ‘new’ delivery system, and file for orphan exclusivity. No new data. Just a different pill shape.

Then we’d jack the price 5000%.

Everyone knew. No one cared.

The FDA doesn’t regulate. They rubber-stamp.

And you? You’re just the sucker paying for the privilege.

Love you, but wake up. 😘

Hank Pannell

January 9, 2026 AT 14:18Let’s unpack the structural asymmetry here: patent law is adversarial, litigious, and subject to judicial scrutiny. Market exclusivity? Administrative, opaque, and functionally unchallengeable.

Patents can be invalidated by prior art. Exclusivity? You need to prove the FDA messed up the application-which requires insider access, legal teams, and millions to litigate.

It’s not a level playing field. It’s a gated community for regulatory capture.

And the 6-month pediatric extension? That’s not incentivizing child health. It’s incentivizing data laundering.

They’re gaming the system with bureaucratic arbitrage.

And the worst part? We call it ‘policy.’

Lori Jackson

January 10, 2026 AT 08:34People who don’t understand exclusivity shouldn’t be allowed to comment on drug policy. You think this is complicated? It’s not. It’s corporate greed dressed up in regulatory jargon.

And you? You’re just another naive idealist who thinks transparency fixes corruption.

Wake up. The dashboard isn’t a tool for accountability-it’s a PR stunt to make you feel better about paying $2000 for a pill.

Every time you say ‘patent expired,’ you reveal how little you know.

And you wonder why healthcare is broken.

It’s because people like you still believe in fair play.

Wren Hamley

January 11, 2026 AT 00:45It’s like the FDA and USPTO are two different gods. One’s a stern judge. The other’s a drunk uncle handing out free tickets to a party no one else can crash.

Patents? You need to prove you invented something. Exclusivity? You just need to prove you spent a lot of money and didn’t cheat too obviously.

And that 180-day generic window? That’s the only time the system gives a damn about competition.

It’s not broken. It’s designed to make you feel like you’re winning while they’re cleaning out the vault.

veronica guillen giles

January 12, 2026 AT 10:04Ohhh, so now we’re supposed to be impressed that the FDA is ‘transparent’ with a dashboard? Sweetheart. That dashboard was built by the same people who wrote the rules.

It’s like giving a fox the key to the henhouse and calling it ‘enhanced security.’

And you think patients are gonna understand all this? Please. Most people don’t even know what ‘NCE’ stands for.

They just know their co-pay went up again.

And you? You’re still writing essays while they’re counting cash.

How’s that working out for you? 😏

Ian Ring

January 13, 2026 AT 02:36Thank you for this-really. It’s rare to see such a nuanced breakdown without hyperbole.

One thing I’d add: the 180-day generic exclusivity period creates a perverse incentive. The first filer often delays launch to maximize profit, knowing no one else can enter until it expires.

So technically, competition is allowed-but it’s deliberately delayed.

It’s not a market. It’s a timed auction.

And the FDA? They’re the auctioneer who gets paid in lobbying dollars.

Still, I’m glad the dashboard exists. Small wins.

erica yabut

January 14, 2026 AT 22:13Colchicine for $5? That’s nothing. I saw a drug go from $1.20 to $1,200 because they added a ‘novel’ tablet coating.

And the people who approved it? They got speaking gigs at pharma conferences.

It’s not a system. It’s a cartel with a license.

And you? You’re still writing blog posts while people die because they can’t afford the pill that’s been around since 1947.

Pathetic.

Tiffany Channell

January 16, 2026 AT 12:56Let’s not pretend this is about innovation. It’s about control. The FDA doesn’t care if the drug works better. They care if the paperwork was filed first.

And if you think generics are the answer-you’re wrong.

They’re just the next phase of the same game. The same companies own them now.

It’s not competition. It’s rebranding.

And you? You’re still falling for the illusion.

Wake up. There’s no hero here. Just profit.

Haley Parizo

January 17, 2026 AT 07:25And yet, here we are. Talking about it. Writing it. Sharing it.

Maybe the real power isn’t in the patents or the exclusivity.

Maybe it’s in the people who refuse to look away.

They can control the drugs.

But they can’t control the truth.

Not forever.