What Is CKD-Mineral and Bone Disorder?

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste. They also stop managing minerals like calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D the way they should. This leads to a complex condition called CKD-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). It’s not just about weak bones-it’s about your whole body going out of balance. By Stage 3 of chronic kidney disease (CKD), nearly 90% of patients already show signs of this disorder. By the time someone needs dialysis, it’s almost universal.

For decades, doctors called this problem "renal osteodystrophy," focusing only on bone damage. But we now know it’s far bigger. CKD-MBD affects your blood vessels, heart, muscles, and even your growth if you’re a child. High phosphate, low vitamin D, and skyrocketing PTH levels don’t just harm your skeleton-they harden your arteries and raise your risk of dying from a heart attack or stroke.

The Three-Part Problem: Calcium, PTH, and Vitamin D

Think of CKD-MBD as a broken feedback loop. It starts with your kidneys losing their ability to filter phosphorus. As phosphorus builds up in your blood (often above 4.5 mg/dL), your body tries to fix it. It ramps up a hormone called FGF23, which tries to push more phosphorus out through urine. But as kidney function drops below 60 mL/min, even that fails.

FGF23 then shuts down the enzyme that turns vitamin D into its active form-calcitriol. Without enough calcitriol, your gut can’t absorb calcium properly. Your blood calcium drops. Your parathyroid glands, sensing that drop, go into overdrive and pump out more parathyroid hormone (PTH). This is called secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Here’s the catch: in advanced CKD, your bones stop responding to PTH. Even with PTH levels over 800 pg/mL, your bones don’t release calcium like they should. This is called "functional hypoparathyroidism." So you have too much PTH, but your body acts like it has too little. Meanwhile, your blood calcium stays low or swings wildly, and your phosphorus keeps climbing. The result? A mess of mineral imbalance that damages both bone and blood vessels.

What Happens to Your Bones?

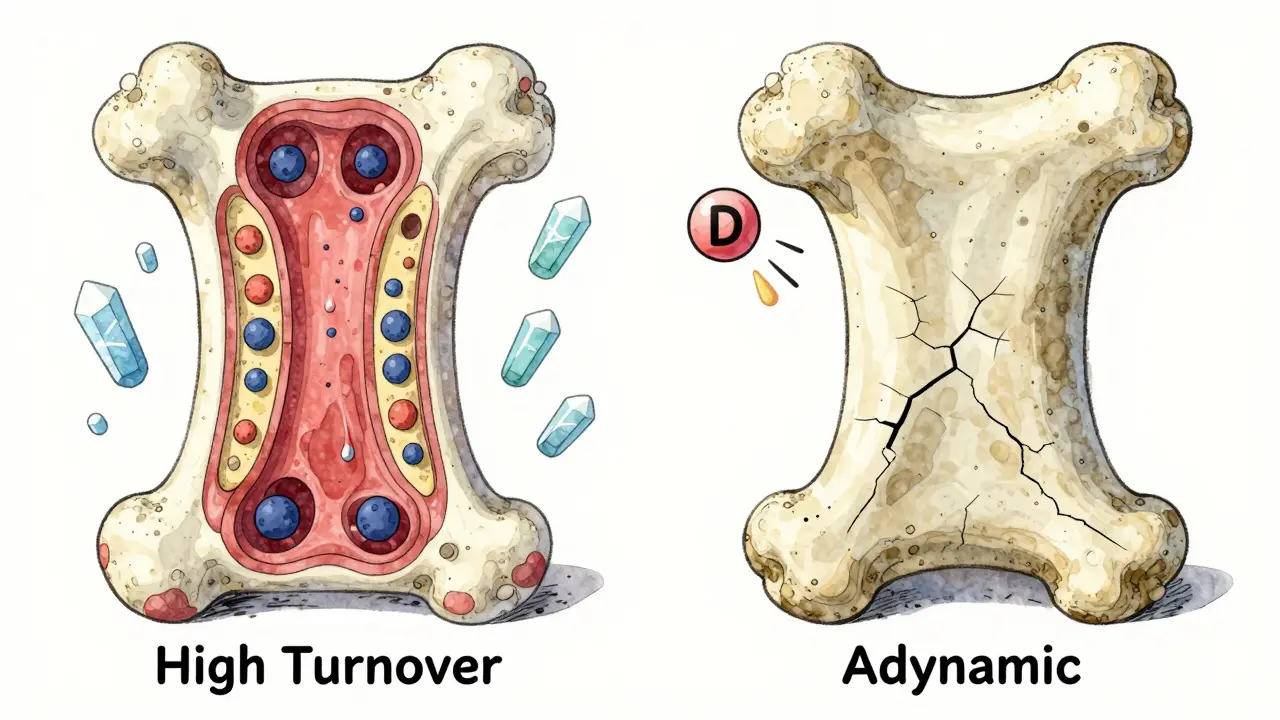

Your bones aren’t just passive storage for calcium-they’re living tissue that constantly rebuilds. In CKD-MBD, that process gets messed up in three main ways:

- High turnover disease (osteitis fibrosa cystica): Your bones are breaking down too fast. PTH levels are sky-high, often above 500 pg/mL. Bone cells called osteoclasts chew away bone faster than osteoblasts can rebuild it. This leads to bone pain, fractures, and deformities.

- Low turnover disease (adynamic bone disease): Your bones barely rebuild at all. PTH levels are low-under 150 pg/mL. Bone formation rates drop below 200 μm² per bone surface per minute. These bones look normal on scans but are brittle. They fracture easily, even without trauma.

- Mixed disease: You get both at once. This happens in 10-20% of dialysis patients and is the hardest to treat.

Adynamic bone disease is now the most common form in dialysis patients, making up 50-60% of cases. It’s often caused by too much calcium-based phosphate binder use or too much active vitamin D. Doctors used to think more PTH was always bad. Now we know too little can be just as dangerous.

Why Your Arteries Are Hardening

One of the scariest parts of CKD-MBD isn’t the broken bones-it’s the calcified arteries. Up to 90% of people on dialysis have calcium deposits in their blood vessels. These deposits start in the walls of your coronary arteries, heart valves, and even your skin. They’re not like cholesterol plaques. They’re actual bone-like material forming where it shouldn’t be.

This calcification doesn’t happen overnight. It progresses at 15-20% per year in dialysis patients. Every 1 mg/dL rise in serum phosphate increases your risk of death by 18%. Coronary artery calcification scores in CKD patients are 3 to 5 times higher than in healthy people. And it’s the leading cause of death: about half of all deaths in people on dialysis are from heart disease linked to vascular calcification.

Why does this happen? High phosphate and low vitamin D trigger cells in your blood vessels to turn into bone-forming cells. Sclerostin, a protein that normally stops bone growth, spikes in CKD and blocks bone repair-while also promoting calcification. Your body is literally turning your arteries into bone.

How Is It Diagnosed?

You won’t feel CKD-MBD until it’s advanced. That’s why regular blood tests are critical. KDIGO guidelines recommend monitoring:

- Calcium: Target 8.4-10.2 mg/dL

- Phosphate: Target 2.7-4.6 mg/dL (Stage 3-5), 3.5-5.5 mg/dL (on dialysis)

- PTH: Target 2-9 times the upper limit of normal for your lab’s assay

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D: Keep above 30 ng/mL

But blood tests only tell part of the story. A bone biopsy is the gold standard for knowing whether your bone turnover is high, low, or mixed. But it’s invasive, so it’s only done in about 5% of cases. Instead, doctors use surrogates: bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP) and PINP (a marker of bone formation) help estimate turnover.

Vascular calcification is checked with plain X-rays (for obvious deposits) or CT scans using Agatston scoring. If your coronary calcification score is over 400, your risk of dying within five years is significantly higher.

Treatment: It’s Not Just About Pills

There’s no magic pill for CKD-MBD. Treatment is about balance-and avoiding one problem while creating another.

Phosphate Control

Most people with CKD need to limit dietary phosphate to 800-1000 mg per day. That means avoiding processed foods, colas, and dairy-heavy meals. But diet alone isn’t enough. Phosphate binders are needed to stop your gut from absorbing what you eat.

Calcium-based binders (like calcium carbonate or acetate) are cheap and effective-but they add more calcium to your system, which can worsen vascular calcification. That’s why KDIGO limits them to 1500 mg of elemental calcium per day. Non-calcium binders like sevelamer or lanthanum carbonate are safer for your arteries but cost more.

Vitamin D Management

Most CKD patients are vitamin D deficient-up to 90% have levels below 20 ng/mL. The first step is nutritional vitamin D (cholecalciferol), given at 1000-4000 IU daily. This helps raise your 25(OH)D level above 30 ng/mL without raising calcium or phosphate.

Active vitamin D (calcitriol or paricalcitol) is reserved for severe secondary hyperparathyroidism (PTH >500 pg/mL). But using it too early or too much can cause dangerous spikes in calcium and phosphate. Recent studies show nutritional vitamin D reduces mortality by 15% without increasing calcification risk.

Controlling PTH

If PTH stays high despite diet and vitamin D, doctors turn to calcimimetics like cinacalcet or etelcalcetide. These drugs trick the parathyroid gland into thinking blood calcium is higher than it is, so it stops pumping out PTH. Cinacalcet reduces PTH by 30-50%. Etelcalcetide, an injectable version, works even better-cutting PTH by 45% in clinical trials.

But here’s the catch: lowering PTH too much can trigger adynamic bone disease. That’s why KDIGO doesn’t recommend targeting a specific PTH number. Instead, they say: treat the patient, not the number. If your PTH is 400 but your bones are healthy and your calcium is stable, you might not need a calcimimetic.

What’s New in 2025?

Research is moving fast. Anti-sclerostin antibodies like romosozumab, which are used for osteoporosis, are now being tested in CKD patients. Early trials show a 30-40% increase in bone mineral density without worsening calcification.

Klotho, a protein that helps your kidneys excrete phosphate, is another hot target. In animal studies, boosting Klotho reduces vascular calcification by 50-60% and improves bone strength. Human trials are still early, but this could be the first therapy that treats both bone and artery damage at once.

The 2024 KDIGO draft update now recommends checking vitamin D levels annually starting at Stage 3 CKD-and monitoring phosphate every 6-12 months. Why? Because FGF23 rises 5 to 10 years before phosphate does. We’re learning that CKD-MBD begins long before you feel sick.

What Should You Do?

If you have CKD, here’s what matters most:

- Get your calcium, phosphate, PTH, and vitamin D checked every 3-6 months.

- Limit processed foods, colas, and added phosphates-read labels. "Phos" on the ingredient list means trouble.

- Take phosphate binders with meals, not before or after.

- Ask your doctor if you need vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and how much.

- Don’t assume high PTH always needs treatment. Ask: Are my bones strong? Are my arteries calcifying?

- Don’t take calcium supplements unless your doctor says so.

CKD-MBD isn’t a single disease. It’s a cascade-one that starts with your kidneys and ends with your heart. Treating just one part won’t save you. You need to manage all three: calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D-along with the hormone that ties them together, PTH. The goal isn’t to hit perfect numbers. It’s to keep your bones strong, your arteries soft, and your heart beating.

Is CKD-MBD the same as osteoporosis?

No. Osteoporosis is bone loss due to aging or hormonal changes, mostly in postmenopausal women. CKD-MBD is caused by kidney failure and involves abnormal mineral levels, high PTH, and vascular calcification. People with CKD-MBD can have low bone turnover (adynamic bone disease), which isn’t seen in typical osteoporosis. Treatments differ too-bisphosphonates for osteoporosis can be dangerous in CKD.

Can vitamin D supplements fix CKD-MBD?

Not alone. Nutritional vitamin D (D3) helps correct deficiency and may lower mortality, but it doesn’t fix high phosphate or high PTH. Active vitamin D analogs (calcitriol, paricalcitol) can suppress PTH but raise calcium and phosphate, increasing calcification risk. The key is using vitamin D wisely-not aggressively.

Why do some doctors avoid calcium-based phosphate binders?

Because they add extra calcium to your body. In CKD, your body can’t excrete excess calcium well. That calcium ends up in your arteries instead of your bones. Studies show calcium-based binders increase vascular calcification and may raise death risk. Non-calcium binders like sevelamer or lanthanum are safer long-term, even if they cost more.

Does lowering phosphate always improve survival?

Not always. While high phosphate is linked to higher death rates, pushing levels below 4.5 mg/dL may cause malnutrition or low bone turnover. Some experts argue that overly strict phosphate targets can lead to protein restriction, which harms muscle and immune function. The goal is moderation-not perfection. A phosphate level of 4.0-5.0 mg/dL is often safer than chasing 3.5.

Can children with CKD recover from bone disease?

Yes, but early intervention is critical. Children with Stage 5 CKD often have growth delays, with height Z-scores -1.5 to -2.0 SD below normal. Aggressive management of phosphate, vitamin D, and PTH can restore growth. Some kids catch up with treatment. Delayed treatment, however, can lead to permanent short stature and skeletal deformities.

Final Thoughts

CKD-MBD is not a side effect of kidney disease-it’s a core part of it. Ignoring calcium, PTH, and vitamin D isn’t just neglecting lab numbers. It’s ignoring the slow, silent damage to your bones and heart. The good news? You can slow it down. With regular testing, smart diet choices, and careful use of medications, you can protect your body from the worst effects. You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to be consistent.

Praseetha Pn

January 18, 2026 AT 10:56Let me tell you something the doctors won't admit-phosphate binders are just a scam to keep you hooked on pills while Big Pharma profits. I read a paper from a guy in Ukraine who said calcium deposits aren't from phosphate-they're from 5G radiation messing with your mitochondria. You think your kidneys are failing? Nah. It's the chips in your water. I've been tracking this since 2019. My cousin on dialysis stopped eating processed food and started drinking filtered rainwater-he's walking again. They don't want you to know this.

Nishant Sonuley

January 18, 2026 AT 16:53Okay, I get that the science here is complex, but honestly, the real issue isn't just the labs-it's how we treat patients like they're broken machines. I've seen people get told to cut out dairy and then handed a $300/month binder prescription with zero dietary coaching. Meanwhile, their grandma’s dal and rice diet, which they grew up on, is perfectly fine. We need to stop treating CKD-MBD like a math problem and start treating it like a life. Also, can we talk about how the word 'adynamic' sounds like a villain in a Marvel movie? It's not helping.

Emma #########

January 18, 2026 AT 19:21I just lost my dad to this. He never complained about bone pain, but he’d sit quietly staring at his hands-fingers stiff, nails brittle. We didn’t know it was CKD-MBD until it was too late. I wish someone had told us to check his phosphate levels earlier. Not because of the numbers, but because he deserved to feel strong until the end. Thank you for writing this. It’s the first time I felt understood.

Andrew McLarren

January 19, 2026 AT 08:29While the clinical framework presented herein is largely consistent with current KDIGO guidelines, I must respectfully submit that the assertion regarding vascular calcification as the leading cause of mortality in dialysis populations warrants further substantiation through longitudinal cohort analysis. The referenced 18% mortality increase per 1 mg/dL rise in serum phosphate appears to conflate correlation with causation, as confounding variables such as inflammation, malnutrition, and concurrent cardiovascular comorbidities are not fully accounted for in the cited literature.

Andrew Short

January 19, 2026 AT 22:03So let me get this straight-you’re telling me we’re supposed to trust a bunch of doctors who prescribed statins to everyone and then acted shocked when people got diabetes? Now they want us to believe phosphate is the villain? Wake up. The real cause of all this is insulin resistance from processed carbs. They don’t want you to know that because then you’d stop eating their government-subsidized corn syrup and start eating meat and butter. You think your bones are weak? It’s your cereal. Your oatmeal. Your ‘heart-healthy’ granola. It’s all poison. And they’re making billions off your ignorance.

christian Espinola

January 20, 2026 AT 08:29There is a grammatical error in the third paragraph: 'It starts with your kidneys losing their ability to filter phosphorus. As phosphorus builds up in your blood (often above 4.5 mg/dL), your body tries to fix it.' The phrase 'your body tries to fix it' is not a scientifically accurate description. The body does not 'try'-it responds biochemically. Also, '4.5 mg/dL' should be written as '4.5 mg/dL' with proper spacing after the number. And 'FGF23' is not capitalized consistently throughout. These errors undermine credibility.

Chuck Dickson

January 20, 2026 AT 23:40Hey-this is actually really helpful. I’ve been on dialysis for 5 years and I’ve been scared to ask my nephrologist about my PTH levels because I didn’t want to sound dumb. But this? This made sense. I’m gonna start reading labels like a hawk. No more ‘phos’ in ingredients. And I’m asking for my vitamin D levels every 3 months. I’m not perfect, but I’m trying. And that’s enough. 💪

Robert Cassidy

January 22, 2026 AT 09:07They say it's about calcium, phosphate, and PTH-but that's just the surface. This is deeper. It's about the collapse of the human body’s natural harmony. The kidneys are the body’s governor. When they fail, it’s not just minerals-it’s the soul’s equilibrium. The West treats the body like a car: replace the part, fix the code. But we’re not machines. We’re stardust trying to remember how to be whole. And they’re selling us binders instead of wisdom. The real disease is forgetting that we’re part of nature, not above it.

Robert Davis

January 23, 2026 AT 04:28Everyone’s talking about binders and labs, but nobody’s talking about the fact that most CKD patients are prescribed too many meds. I’ve got 17 pills a day. I don’t know what half of them do. And now they want me to take another one for PTH? I’m not a pharmacy. I’m a person who just wants to eat a meal without calculating phosphate content like a chemist. I’m tired.

Max Sinclair

January 24, 2026 AT 11:06Great breakdown. I especially appreciated the part about adynamic bone disease being more common now. I had no idea that too much vitamin D or calcium binders could cause it. I’m gonna ask my doc about my BSAP levels next visit. Also, the note about FGF23 rising years before phosphate? That’s wild. Makes me want to get tested even if I’m still in Stage 3. Thanks for the clarity.

Naomi Keyes

January 26, 2026 AT 09:41Let me just say-this article is dangerously incomplete. You mention Klotho, but you fail to cite the 2023 Nature paper by Dr. Lin from Stanford, which demonstrated that Klotho gene expression is suppressed by glyphosate exposure. You also ignore the fact that the FDA has approved 3 new phosphate-lowering agents since 2022, which are not mentioned. And you use the term 'adynamic' without defining it in layman's terms. This is not medical advice-it's a half-baked blog post with citations missing. Shameful.

Dayanara Villafuerte

January 27, 2026 AT 08:36OMG YES. 🙌 I’m a dietitian in LA and I’ve been telling my CKD patients for YEARS: ‘Phos’ on the label = run. 🏃♀️💨 And no, your ‘healthy’ protein bar is not healthy-it’s basically a phosphate bomb. I even made a cheat sheet: ‘NO PHOS’ = NO PROBLEMS. I’ll send it to you if you want! Also, vitamin D3? Yes. Active D? Only if your PTH is sky-high and your bones are screaming. Don’t be a hero. 🌿💊

Andrew Qu

January 29, 2026 AT 04:13One thing I’ve learned working with CKD patients: consistency beats perfection. You don’t need to hit every lab target. You just need to show up. Take your binder with your meal. Get your blood drawn. Talk to your dietitian. Even if you slip up and eat a bag of chips, you’re still ahead of the game just by being aware. It’s not about being perfect-it’s about being present. You’ve got this.

kenneth pillet

January 31, 2026 AT 00:39good info thanks. i didnt know about the bone biopsy thing. i thought they just looked at blood tests. also i think the part about arteries turning to bone is wild. kinda creepy but makes sense. i’ll start checking labels

Praseetha Pn

February 1, 2026 AT 07:18Of course you think it’s just about diet and binders. But what about the fluoridated water? The aluminum in antacids? The vaccines? They’re all linked. I’ve seen it in the data. Your kidneys don’t fail because of age-they fail because of the poison they’re forced to filter. The WHO knows. The CDC knows. They just won’t say it. I’ve got a spreadsheet. 172 cases. All on dialysis. All had fluoride in their water. Coincidence? I think not.