Managing diabetes isn’t just about taking pills or injecting insulin-it’s about staying safe while doing it. Every year, thousands of people end up in emergency rooms because of medication mistakes. Some take too much insulin. Others don’t realize their blood sugar has dropped too low. A few even start a new antibiotic without knowing it can make their diabetes meds dangerous. This guide cuts through the noise and gives you real, practical safety info on insulin and oral diabetes drugs-what works, what risks to watch for, and how to avoid the most common mistakes.

How Insulin Works and Where Things Go Wrong

Insulin isn’t one thing. It comes in different types, each with its own timing and risks. Rapid-acting types like lispro and aspart kick in within 15 minutes and last 3-5 hours. Long-acting ones like glargine and degludec last up to 24-42 hours. But here’s the catch: if you mix them up, or use the wrong dose, things can get dangerous fast.

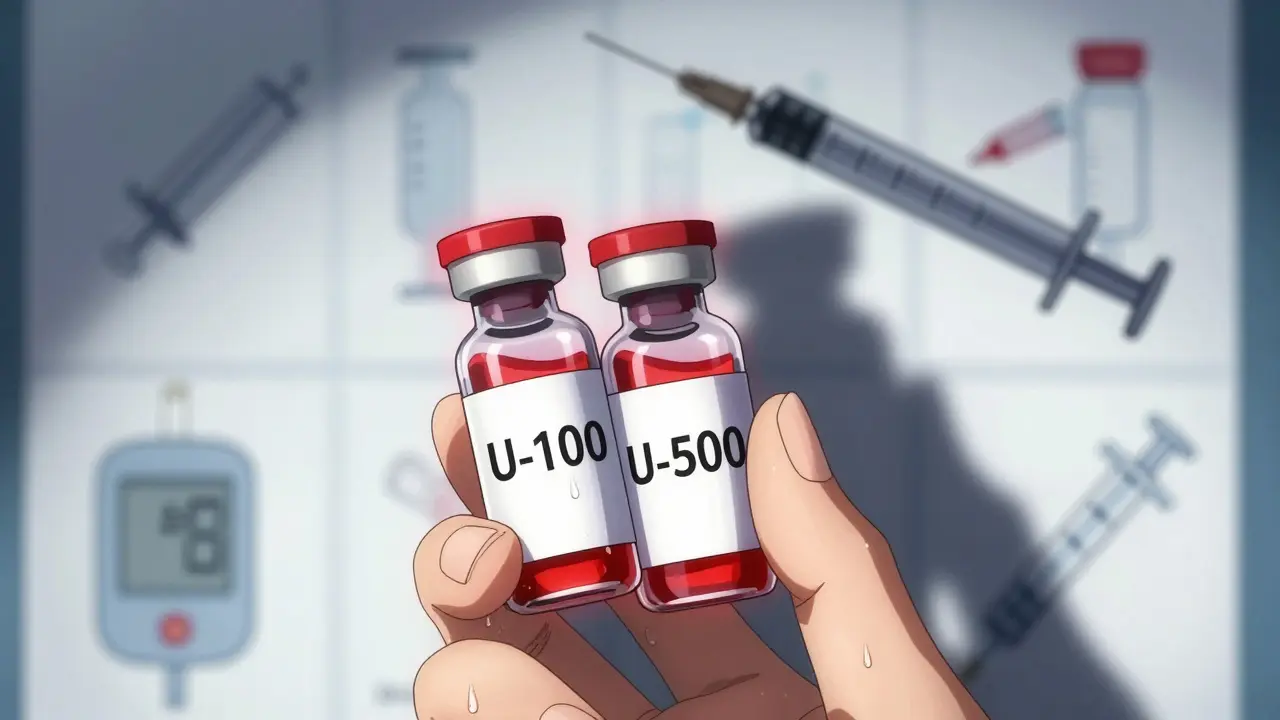

One of the most serious mistakes? Confusing Humulin R U-500 with regular U-100 insulin. U-500 is five times stronger. If someone thinks they’re giving 10 units of regular insulin but actually gives 10 units of U-500, they’ve just injected 50 units. That’s enough to cause life-threatening hypoglycemia. There are real cases of this happening because patients didn’t know the difference-or their pharmacy didn’t label it clearly.

Another big issue is injection technique. Injecting into muscle instead of fat can make insulin absorb too fast, causing sudden drops in blood sugar. Rotating injection sites isn’t just about avoiding lumps-it prevents unpredictable absorption. Skipping rotation means uneven insulin delivery, which throws off your whole day’s control.

Oral Medications: The Hidden Dangers

There are more than 10 types of oral diabetes drugs, but only a few carry major safety risks. Metformin is the go-to first-line treatment. It’s safe for most people-but not if your kidneys aren’t working well. The FDA says don’t start metformin if your eGFR is below 30. If it’s between 30 and 45, use it with caution. Between 45 and 60? Cut the dose. Many doctors forget this. Patients with kidney disease end up with lactic acidosis-a rare but deadly buildup of acid in the blood.

Sulfonylureas like glipizide and glyburide are cheaper and effective, but they’re also the biggest cause of low blood sugar. Studies show 20-40% of people on these drugs have at least one hypoglycemic episode a year. For older adults, that number jumps. One study found 30% of well-controlled type 2 patients on sulfonylureas had silent nighttime lows-no shaking, no sweating, no warning. Just sudden confusion, falls, or even seizures.

Glipizide is safer than glyburide in kidney patients because it’s broken down by the liver, not the kidneys. But many prescriptions still default to glyburide. That’s outdated practice. Ask your doctor: Is this the right sulfonylurea for my body?

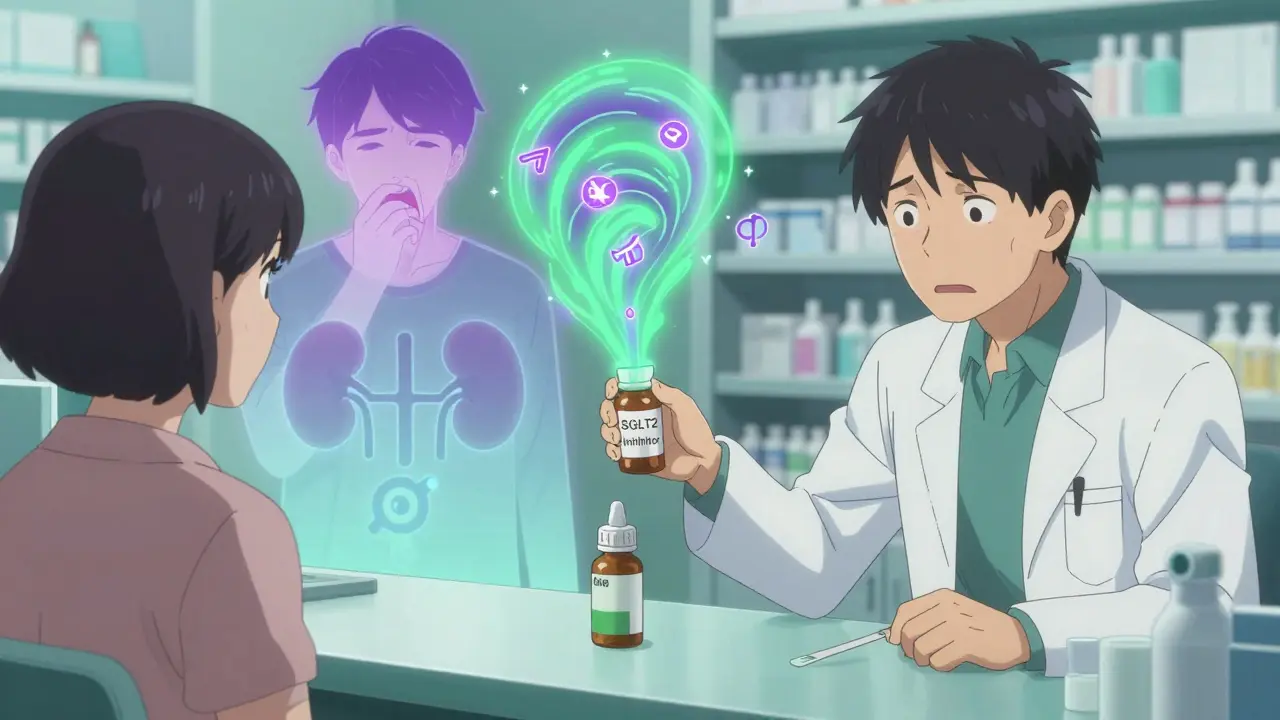

Newer Drugs: Benefits With New Risks

Drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) and GLP-1 agonists (semaglutide, tirzepatide) are popular because they help the heart and kidneys-not just blood sugar. But they come with new dangers.

SGLT2 inhibitors can cause diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), even when blood sugar isn’t high. This is called euglycemic DKA. It’s rare-only 5-10% of DKA cases in these patients-but deadly if missed. The FDA warns: stop these drugs at least 24 hours before surgery, during serious illness, or if you’re vomiting and can’t eat. If you feel nauseous, tired, or have stomach pain while on one of these, check for ketones. Don’t wait for high blood sugar to react.

GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic and Mounjaro cause nausea in 30-50% of users, especially at first. Many quit because of it. But the real danger? People stop taking them cold turkey and then binge on carbs. That spikes blood sugar hard. Always taper off slowly under medical supervision.

Genital yeast infections are another common side effect. About 4-5% of women on SGLT2 inhibitors get them. Men get them too. It’s not dangerous, but it’s embarrassing and recurring. If you’re prone to yeast infections, talk to your doctor before starting one of these.

Drug Interactions You Can’t Afford to Ignore

Diabetes meds don’t live in a vacuum. They react with other drugs you’re taking.

Antibiotics like sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (Bactrim) can boost insulin’s effect. One Reddit user shared how he got hospitalized after starting Bactrim for a UTI. His blood sugar dropped to 42 mg/dL overnight. He didn’t know to reduce his insulin.

Other risky combos: quinine (for leg cramps), sunitinib (cancer drug), and somatostatin analogues (for pituitary tumors). All increase hypoglycemia risk. Even over-the-counter stuff like aspirin and NSAIDs can interfere-especially in older adults.

Always give your pharmacist your full med list. Not just prescriptions. Include vitamins, herbal supplements, and OTC painkillers. Many don’t realize that St. John’s Wort can reduce metformin’s effectiveness.

Special Risks for Older Adults

One in four hospital admissions for diabetes complications involves someone over 65. Why? Three things: hypoglycemia unawareness, slower metabolism, and fall risk.

As we age, our bodies stop warning us when blood sugar drops. No sweating. No shakiness. Just dizziness-and then a fall. Banner Health data shows dizziness from meds leads to fractures and head injuries in older patients more often than people think.

Start low, go slow. For older adults, doctors should begin sulfonylureas at half the usual dose. Aim for looser targets: HbA1c around 7.5-8% instead of 6.5%. Tight control isn’t worth the risk if it means a broken hip.

Also, check kidney function every 6 months. Many seniors take metformin for years without ever getting an eGFR test. That’s how lactic acidosis sneaks up.

What You Can Do Right Now

Here’s how to stay safe, starting today:

- Write down every med-name, dose, time, reason. Keep it in your wallet or phone.

- Know your insulin type. If you’re on U-500, confirm with your pharmacist: Is this U-100 or U-500?

- Check your eGFR at least once a year. If you’re on metformin, ask: Is my kidney number still safe?

- Get a ketone test strip if you’re on an SGLT2 inhibitor. Keep one in your medicine cabinet.

- Never skip meals on sulfonylureas or insulin. Even one missed meal can trigger low blood sugar.

- Use a glucose monitor at night if you’re over 65 or on insulin. Silent lows are real.

- Ask about automated insulin delivery if you’re on multiple daily injections. Studies show it cuts hypoglycemia by 30%.

When to Call Your Doctor

Don’t wait. Call right away if:

- You’ve had two or more low blood sugar episodes in a week

- You feel dizzy, confused, or nauseous without a clear cause

- You’re scheduled for surgery or a procedure

- You’ve started a new medication, even an OTC one

- Your urine smells sweet or fruity (sign of ketones)

Diabetes meds save lives-but they can also hurt you if you don’t know the risks. The goal isn’t perfect numbers. It’s staying out of the hospital, staying strong, and living well. Know your drugs. Know your body. And never be afraid to ask questions.

Can I take metformin if I have kidney disease?

Metformin can be used with caution if your eGFR is between 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73m², but the dose must be reduced. If your eGFR is below 30, you should not take metformin at all. Many doctors still prescribe it without checking kidney function, which can lead to lactic acidosis-a rare but life-threatening condition. Always get your eGFR tested before starting or continuing metformin.

Why do SGLT2 inhibitors cause ketoacidosis even with normal blood sugar?

SGLT2 inhibitors make your kidneys remove sugar through urine. This lowers blood sugar, but it also shifts your body into fat-burning mode. If you’re dehydrated, sick, or not eating enough, your body can overproduce ketones. This is called euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Blood sugar may only be 150-250 mg/dL-not the 400+ you’d expect. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fatigue. If you’re on one of these drugs and feel unwell, test for ketones immediately-even if your sugar seems fine.

Is insulin more dangerous than oral pills?

Insulin carries a higher risk of severe hypoglycemia than most oral drugs, especially if doses are miscalculated or timing is off. But oral drugs like sulfonylureas (e.g., glyburide) are also high-risk for lows. The real difference is control: insulin can be adjusted quickly based on food and activity. Oral drugs like sulfonylureas keep working for hours, even if you skip a meal. That’s why insulin, when used correctly with monitoring, can be safer than some oral agents.

What should I do if I accidentally take too much insulin?

If you think you’ve taken too much insulin, eat fast-acting carbs immediately: 15 grams of glucose tablets, 4 ounces of juice, or 1 tablespoon of sugar. Check your blood sugar every 15 minutes. If it doesn’t rise, take another 15 grams. Keep eating even if you feel fine-hypoglycemia can return hours later. Call your doctor or go to the ER if you feel confused, weak, or can’t wake up. Never drive or operate machinery until your sugar is stable for at least two hours.

Can I stop my diabetes meds if I lose weight or change my diet?

Weight loss and diet changes can improve blood sugar control, but never stop meds without talking to your doctor. Stopping suddenly can cause rebound high blood sugar or even diabetic ketoacidosis. Some people can reduce doses, but that needs careful monitoring. Your doctor may suggest lowering your dose gradually while checking your HbA1c and glucose levels daily for at least two weeks.

Cory L

February 22, 2026 AT 10:29Southern Indiana Paleontology Institute

February 24, 2026 AT 09:16Anil bhardwaj

February 25, 2026 AT 19:16lela izzani

February 27, 2026 AT 04:33Joanna Reyes

February 28, 2026 AT 01:58Nerina Devi

February 28, 2026 AT 02:53Dinesh Dawn

March 1, 2026 AT 14:12Vanessa Drummond

March 1, 2026 AT 17:57